Science Storytelling with Comics, an Interview with Maki Naro

“Science can be fuzzy, dark, and obtuse. There becomes a point where words fail and it’s easier to just draw a picture.” says comic artist Maki Naro who — according to Scientific American — brings “‘serious artwork’ to the science comic world”.

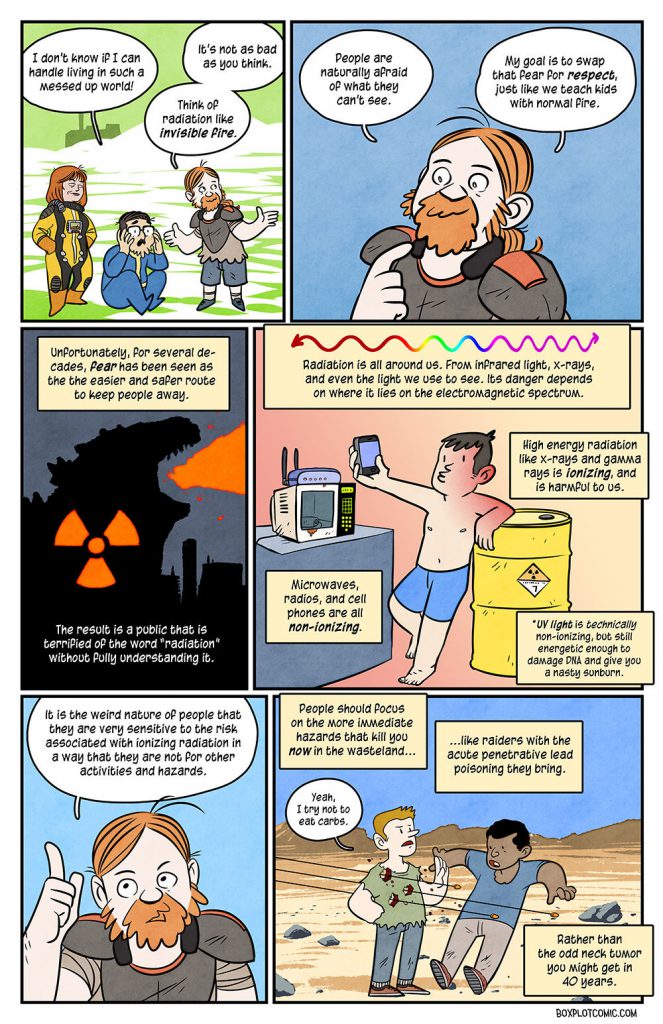

Maki Naro is a comic artist, illustrator and science communicator living in New Jersey. His comics range in topics from the effects of radiation on human and natural life in the “Fall(Out) Guy” series from Box Plot blog of Popular Science, to the efficacy of vaccines in “Vaccines Work. Here Are the Facts” from The Nib. Here, we ask Maki what his views are of comics and its role in science communication and dissemination.

1. Hi Maki! What inspired you in the first place to start creating science comics?

In 2010, I had been out of art school for six years, living in New York City, and working long hours in which I performed repetitive tasks and listened to science podcasts all day. I didn’t have much time for art, and it was really bumming me out. One day I met a musician I admired who wrote songs about science, and a light bulb turned on in my head: I could draw comics about science. It was perfect. I was constantly ingesting material in the form of podcasts, and having a webcomic would force me to draw every day. Suffice to say, it worked. A friend of mine joined me and we started drawing comics every other day for fun. Another six years later, and it’s been a wild ride with me working for a major New York City science festival, joining the Popular Science blog network, and even competing in a webcomic reality show.

In 2010, I had been out of art school for six years, living in New York City, and working long hours in which I performed repetitive tasks and listened to science podcasts all day. I didn’t have much time for art, and it was really bumming me out. One day I met a musician I admired who wrote songs about science, and a light bulb turned on in my head: I could draw comics about science. It was perfect. I was constantly ingesting material in the form of podcasts, and having a webcomic would force me to draw every day. Suffice to say, it worked. A friend of mine joined me and we started drawing comics every other day for fun. Another six years later, and it’s been a wild ride with me working for a major New York City science festival, joining the Popular Science blog network, and even competing in a webcomic reality show.

2. I noted that your work shares a similar format of explaining science as the comics collections “Anthropocene Milestones”. Has it been a source of inspiration?

I’ve actually never seen this before and am reading it all now! It’s fantastic! Early on, I took a lot of inspiration from Darryl Cunningham’s work. He has a great talent for explaining complex subjects in a clear manner. I’m also very inspired by Ben Lillie’s storytelling show, Story Collider. He focuses on the human side of science, which is something I have been striving to do lately.

3. In your opinion, what are the strengths and weaknesses of comics as a format for science communication and dissemination?

I’m probably a bit biased, but I don’t think there are really any weaknesses as far as communicating science to a lay audience goes. Perhaps it wouldn’t be the best medium for turning in your PhD thesis, but, then again, a friend of mine went did it and it’s such a good book (http://www.veronicaberns.com/atomicsizematters/). The strengths lie in the nature of comics as a visual narrative. Science can be fuzzy, dark, and obtuse. There becomes a point where words fail and its easier to just draw a picture. So for as long as there have been scientists, there have been science illustrators (back in the day, the same person usually did both!). Comics merely add a narrative element to it, which is important because science is about people and their stories more than anything. When I joined PopSci, I renamed my comic Boxplot as a pun on the statistical graph and because comics are “boxed plots” for that very reason. Science is the story of how humans have come to understand the world they live in.

Keeping the humanity in science may not seem overly important, but there’s a tendency for science popularizers to treat science as an infallible monolith. In the interest of getting more people on board with science, the human aspects get swept under a rug. But it’s important for the public to know that science doesn’t do science, people do science. The fact that women and minorities still face hurdles when trying to become scientists is all the evidence you need that science doesn’t operate outside society. The controversy surrounding the proposed telescope on Mauna Kea is all the evidence you need that science is still often done for the benefit of one group at the expense of others. This is why you’ll find my comics sometimes address social issues within the scientific community. Comics have a rich history of criticism and satire, and I draw (ha ha) from this whenever I can to do more than just convey facts in a creative manner. Comics have a great potential to teach all sorts of lessons.

I can never pick just one. I could spend hours trying to decide and still end up with a list of 100 artists. I’m really enjoying the Saga series by Brian K. Vaugn and Fiona Staples and I Kill Giants by Joe Kelly and J. M. Ken Niimura, is one of my favorite books of all time. For science comics I highly recommend Rosemary Mosco’s work (either Bird and Moon or Wild City) if you’re a fan of the natural world.

I can never pick just one. I could spend hours trying to decide and still end up with a list of 100 artists. I’m really enjoying the Saga series by Brian K. Vaugn and Fiona Staples and I Kill Giants by Joe Kelly and J. M. Ken Niimura, is one of my favorite books of all time. For science comics I highly recommend Rosemary Mosco’s work (either Bird and Moon or Wild City) if you’re a fan of the natural world.

I can never tell if science comics are growing, or if I’m just noticing them more. Even in the course of this interview, I’m learning about new works. I think the value of comics as a medium for science communication is certainly growing and being recognized across the board. I hope it inspires more and more people to take up the pen and draw.

- Making math and quantum physics fun with Chris Ferrie - March 28, 2018

- Book review: The Animal Cell (Think-A-Lot-Tots series) - January 25, 2017

- Baking + Science = Bio-Bodies Bake Off - December 23, 2016

- Video: an effective tool for disseminating complex research - December 12, 2016

- A new way to visualize molecular models with Molecular Flipbook - September 8, 2016

- Fostering a better-educated community — the Hamed Mirzaei Foundation - July 5, 2016

- Science Storytelling with Comics, an Interview with Maki Naro - June 15, 2016

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!