Maria Baghramian is a Full Professor of Philosophy at University College Dublin and a member of the Royal Irish Academy. She was the Principal Investigator, with the astrophysicist Luke Drury as a co-investigator, of the Irish Research Council project When Experts Disagree. Currently, she co-ordinates the Horizon 2020 research project Policy, Expertise and Trust in Action (PEriTiA). The project received a grant of 3 million euro from the European Commission and will be running from 2020-2023.

Thank you very much for accepting this interview, Prof. Baghramian. To give the readers some context, you are part of the ALLEA (All European Academies) working group that produced a number of reports on “Truth, Trust and Expertise”. Could you please tell me what prompted this report? Why was it important to look into this issue, and why now?

The “Truth, Trust and Expertise” (TTE) working group, a joint initiative of the British Academy and ALLEA, began its work in 2017 when The Oxford English Dictionary had designated “post-truth” as the word of the year and soon after Michael Gove, a pro-Brexit British minister, had claimed that “the British people have had enough of the experts”, while Donald Trump had announced that he had “always wanted to say this… the experts are terrible”. There was a sense in the academia, one that has not yet abated, that the very idea of truth and knowledge were under attack and that some concrete counter-measures were needed. Our response to what is often characterised as a crisis of both truth and trust, was to produce three working papers on themes of trust, trustworthiness in science and the role of social media in enhancing or undermining truth and trust.

What would you say is the main finding of this report?

As it befits their subject matter, the reports were detailed and nuanced. The TTE working group started its deliberations by arguing that trust involves deferring to others, with some level of confidence, on matters that are beyond our knowledge or power. Trust is essential to our social and interpersonal interactions, but it also involves a risk because in trusting we make ourselves vulnerable to betrayal. Establishing and renewing trust in science are of paramount importance in two distinct ways: trust within science gives researchers the confidence to rely on each other’s results and methods and to collaborate more effectively. Warranted trust in science by the general public is also needed because science it is increasingly playing a central role in policy decisions, for instance on matters related to health, the environment, and food production. Trust in the practices and the findings of scientists by the general public and policy makers is crucial for implementing public policies informed by scientific advice. This dual requirement of trust in science is nowhere more obvious than in the post-Covid19 world, where scientists are working at great speed and under conditions of uncertainty to combat the virus and policy makers are proposing draconian public measures based on expert advice.

The TTE working group also investigated the role of the media, particularly the new forms of it, in the changing patterns of trust and distrust and how radical shifts in the context and modes of communication have undermined traditional patterns of trust. Our new project, PEriTiA, with participation from members of the original working group and many others, is following these topics in greater detail. One event that may be of interest to your readers is a major online conference on Trust in Expertise in a Changing Media Context, taking place in March 18th and 19th, 2021.

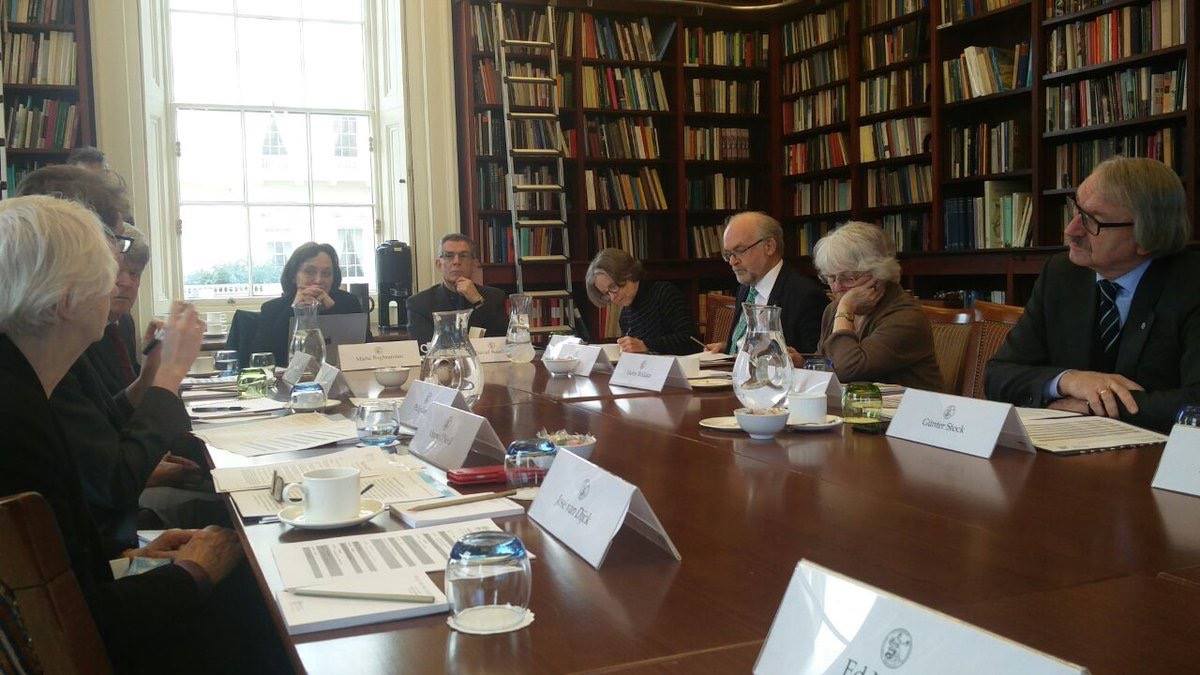

The “Truth, Trust and Expertise” (TTE) working group at their initial meeting.

I noticed the report makes a point of distinguishing between and highlighting both trust and trustworthiness. Would you say these are different things, and why is it important that we consider them separately?

The question of who we should trust is often posed as the main dilemma facing us in times of social crisis and extreme upheaval. But the answer to the question “who to trust?” is quite simple: we should only trust the trustworthy and distrust the untrustworthy. Both misplaced trust and unwarranted distrust can pose serious societal and interpersonal problems. The real challenge then is to find measures and criteria for who is worthy of the risk of trust. We should not place trust where none is warranted but, at the same time, we need to avoid what Baroness Onora O’Neill, the co-chair of TTE, has called the Cassandra Problem: the problem of misplaced distrust where, as in the case of vaccine hesitancy or climate scepticism, an attitude of distrust can lead to a great deal of harm. The question “who is trustworthy?” is of course complex and the response will vary with contexts, but fortunately, when it comes to science and expertise, there are some clear criteria that can help us distinguish the trustworthy scientists from the untrustworthy.

The “Truth, Trust and Expertise” (TTE) working group during one of the workshops that created the final reports.

Should society trust expertise and, in particular, science? Do you see trust in science as a benefit or a threat to democracy? Are there lines that separate these two things that society should be wary of crossing?

Scientific expertise is increasingly woven into the fabric of our lives. Science, indirectly through technology and directly through policy advice, shapes our life choices. Despite a common misperception, scientists and medical doctors are among the most trusted professionals. Experts are deemed trustworthy based on their track record of competence and training, as well as their honesty and integrity. Good will is a further important constraint on the trustworthy scientist. Trusted experts are expected to ensure, to the best of their abilities, that their work and advice leads to more good than harm.

Science impinges on politics directly when it becomes an instrument of policy decisions. It is the use made of science that can be of benefit or a threat to democratic values. So I don’t think science itself can be anti-democratic, but how it is supported, and its results put into effect, may be supportive of or detrimental to democratic values. I would also like to add that the ideals of science are in themselves a good model of how democracy can be conducted. Science at its best, is meritocratic and ready to admit its fallibility. Its results are provisional and (self-)criticism is essential to its conduct. These core features of the scientific method, and they are also useful tools for democratic discourse.

Personally, I think “Truth, Trust and Expertise” is a fascinating topic of great importance to society. I was glad to see that the report not only analyses the issue but also makes suggestions going forward. However, do you think this discussion is getting ‘stuck’ in academic circles? How do we bring these debates around trust and trustworthiness to mainstream discourse?

I believe there are clear benefits to conducting purely academic studies of the ideas of trust, truth and expertise. Without a firm and clear grasp of these concepts, and the contour of the problems surrounding them, we cannot have adequate resolutions of the crisis of truth and trust. Having said that, I think research on such momentous topics should not remain ‘stuck’ in academic circles and this is exactly what our new project, PEriTiA, attempts to avoid. The project runs in three stages: the first focuses on theoretical questions about expertise and trust drawing on the work of philosophers, psychologists, sociologists and media experts. The second will start next year and relies on surveys and laboratory experiments to investigate how the general population across seven European countries thinks about trust in experts. The final phase is where we are hoping to establish a direct linkage between our theoretical and empirical findings and public discourse about trust in experts. To that end, we are organising encounters and open discussions between ordinary citizens, experts and policy makers through so-called mini publics or small scale citizen assemblies. In this way, we hope that our findings will be enhanced by the views of the general public and may also be directly of use to them.

Group photo taken at the launch of the PEriTiA H2020 Project in March 2020, taken at the Newman House, St Stephens Green, Dublin. Photograph Nick Bradshaw.

What do you think is the main challenge the science community faces today in attempting to earn people’s trust?

Currently the greatest challenge to the science community I think is the spread of disinformation and conspiracy theories, aided and encouraged by populist strongman politicians, and made possible by various social media channels and the algorithms they use in spreading both information and misinformation. Conspiracy theories, fake news, propaganda have been constant features of public life, particularly at times of crises and uncertainty, but social media have created unparalleled opportunities for their organised and systematic dissemination and have turned them into powerful tools against science and knowledge.

Do you have any tips for early career scientists who may be considering embarking on their own science communication initiatives? How can they develop a trustworthy relationship with their audience?

As the response to an earlier question signalled, I am a great believer in establishing direct contacts between scientists and the general public. Early career scientists increasingly work in large clusters and labs; these working arrangements can provide opportunities to organise “science cafes” and open science fora where scientists explain their research and address questions from the public. The proceedings of such encounters could then be made available through videos and podcasts and thus become further occasions for opening science to public scrutiny. Openness and accountability are proven markers of trustworthiness.

- Turning frustration into change: Jean-Sébastien Caux, founder of SciPost - August 9, 2021

- Dr Nicola Nugent: Publishing Manager at the Royal Society of Chemistry - December 7, 2020

- Public Engagement and Trust in Science: In Conversation with Dr. Farzana Meru - November 23, 2020

- Is the peer review process trustworthy? Perspectives by Dr. Jurado Sánchez - November 4, 2020

- Prof. Maria Baghramian: Policy, Expertise and Trust in Action - October 29, 2020

- Prof. Luke Drury: ‘When Experts Disagree’ - October 5, 2020

- Are we what we hear? A reflection on sound, identity and science communication - September 27, 2020

- Sign your Science - September 22, 2020

- Raven the Science Maven - August 18, 2020

- Dr Mark Temple: DNA Sonification or when Scientist are musicians - August 5, 2020