Ashmolean in Oxford produces videos about the history of mathematics

Oxford mathematics recently joined forces with the Ashmolean Museum to produce some excellent video essays on themes from the history of mathematics: Random Walks. In this interview, project leader Thomas Woolley offers a step-by-step protocol for other research museums to follow.

Dr. Thomas Woolley, St John’s College, University of Oxford

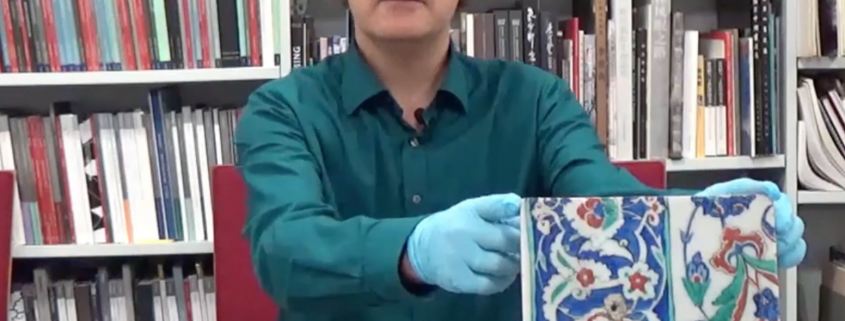

In order to demonstrate “the history of mathematics and the mathematics of history” Oxford Mathematical Institute teamed up with the the Ashmolean Museum. In three short videos—which could be described as essays, rather than lessons or documentaries—“Oxford mathematicians roam the Museum, stopping to take in the mathematics of Babylonian tablets, the joy of maps and the beauty and symmetry of ancient tiles.”

A random walk is actually a mathematical object: it describes a path that consists of a succession of random steps — for example the path traced by a molecule moving about in a gas.

Crastina got in touch with project leader Thomas Woolley.

Hi Thomas! Tell us a little about the Random Walks project. How was it concieved from the start?

Random walks was conceived over lunch. I was talking to Dr Catherine Whistler, who works closely with the Ashmolean museum. She knew I did a lot of mathematical outreach and asked me how I would get scientists interested in a history museum. You see, the Ashmolean museum is a research museum, thus, alongside presenting ancient and rare artefacts for the public to see, the objects are investigated by some of the world’s leading historians, archaeologists and anthropologists. However, scientists and mathematicians are missing from that list and we wanted to change that.

What’s your own background! Have you worked at the BBC?

I am a member of the Wolfson Centre for Mathematical Biology (WCMB). My research focuses on modelling biological systems in order to get a better understanding of how certain biological phenomena occur. Specifically, I work on the mathematics of animal skin patterns, as well as understanding the motion of muscle stem cells.

When not doing mathematics I am a keen participant in mathematical outreach workshops and have given a variety of popular maths lectures. I have had the fortune of working for the BBC on a documentary series called The Code, which illustrated how our complex universe could be understood through simple mathematical rules. I’ve also illustrated Marcus du Sautoy’s book, The Number Mysteries, and worked on the popular maths show Dara O’Briain’s School of Hard Sums.

Most recently I worked with the London Science Museum as their “Fellow of Modern Mathematics”. Essentially, I was the person who had to interpret all of the objects in the galleries in terms of their mathematical content. The two galleries I worked on, Wonderlab and the History of Mathematics gallery, have both just opened and it is wonderful to finally see the incredible objects that illustrate the rich history of mathematics.

How did you proceed with the planning and the organisation? Please explain in numbered steps!

I don’t try to plan too hard. Nothing ever goes exactly to schedule, thus, you have to be willing to move with the outcomes that occur. The more flexible you can be the more options you have. Having said that, below is the process I went through to create each video.

1) I went around the museum and made a list of all the objects I could give a mathematics story for. Sometimes this was from my own knowledge, sometimes this was from the labels in the museum. For example, without the Ashmolean’s texts I would never have known the rich mathematics behind the clay tablets that I presented.

2) I contacted other mathematicians who were interested in helping out. They also had a walk around the museum and we all wrote scripts.

3) Editing is extremely important. When working on your own material it is very easy to lose sight of clarity because you know all the details. Thus, I made sure that my script was seen by a number of mathematicians and non-mathematicians to ensure that my message would come across clearly.

4) I got in contact with the Ashmolean through Sarah Docherty, their Public Engagement Assistant. Through this I was able to set up museum access times and any permissions I needed to present the objects.

5) I was lucky that Mareli Grady, the Oxford Mathematics Outreach Facilitator, had been recently learning how to make films. She was extremely obliging in doing the camera work and she had a great eye for framing the scenes.

6) The equipment was loaned to us from Oxford’s Mathematical and Physical Life Sciences Department. The equipment was intended for outreach use and, thus, they were extremely happy for us to use it.

7) Once I had the equipment, the camera woman, the access and the script all lined up, the filming was quite easy, usually just taking a single morning.

8) The longest part was the editing process. First I went through all the video files and cleared all the ones with mistakes. Then I named each file stating it’s contents, its quality and whether, or not, we had multiple camera angles of the same shot.

9) Then I began to piece the bits of footage together using the script as a backbone to work around. This was the part that needed most flexibility, as you might find you didn’t quite get the shot you wanted. In such cases I would often use the audio from the video files, but then create an animation to illustrate the discussed topic.

10) Once a rough edit of all the animations and footage were in place I then started to add the final touches, such as smooth transitions and background music.

11) Before I published the videos I, once again, ensured I got people’s opinions. What in the videos worked? What didn’t? Where did the pace drop? What parts where not clear?

12) Finally, after including all of the comments and clarifications from point 11 I published the videos and gave them to the maths department and Ashmolean to host wherever they liked.

In terms of software, I mostly used free software, such as: Gimp for animations and graphical editing; HitFilm Express for video editing and Audacity for sound editing.

What are the three most important things to think about to get a good result?

1) Start with your audience. Who do you want to watch the video? What will they know? What gaps will you need to fill?

2) Getting at least one other person to edit your work is crucial. Very often a creator is too close to their work to really see if something is not working. The first random walks video (my one) changed completely from its first incarnation. From showing early drafts to people I could see that I was trying to pack too much in and I had to cut numerous pieces of footage. It was hard to do, but the final video was much better for it.

3) No money has to be spent to generate a nice piece of media. If you have the money, then buying the latest piece of software, or equipment will make your life easier as they are usually engineered to allow the user to simply produce nice work. However, as I suggested above, nearly all of the software and equipment I used was either free or borrowed. Critically, the equipment doesn’t automatically imbue the user with talent. Quality comes from the time invested in understanding how best to use the equipment that you have.

Which are your personal three YouTube favourites?

Captain Disillusion is incredible. His videos are first rate in terms of content, effects, humour, story, visuals and animations. You can really see how passionate he (and his production team) is about making high quality videos.

Full disclosure: I have no connection with this creator.

Scam School, hosted by Brian Brushwood. This may seem a strange youtube channel to include as they present themselves mainly as a bar scam/magic channel. However, their videos include a number of demonstrations that are mathematical, or scientific in flavour. since they’re intended to be “bar scams” they invariably require very little set up and have minor dependence on props. Thus, I can often learn new tricks that can be fed into my mathematical outreach repertoire

Full disclosure: I have no connection with this creator.

I like my science quick. Not because I don’t like the detail, but there is so much out there that you have to be very discerning in what you follow and what you read into. Minute Earth gives a huge variety of brief, well researched tutorials. This gives me a global view of what is going on and is a jumping off point for deeper research into the critical ideas.

Full disclosure: I have worked with this creator on their Turing pattern videos.

- Claire Price of Crastina receives outreach award from Royal Society of Biology - October 25, 2020

- Agile Science student project at Brussels Engineering School ECAM: “We can’t wait to try it again!” - August 28, 2020

- Create an infographic in the Lifeology SciArt Infographic Challenge - June 16, 2020

- Adam Ruben – The scientist that teaches undergraduate students comedy - March 27, 2020

- Sam Gregson, Bad Boy of Science: “Comedy helps to bridge the gap” - March 10, 2020

- The Coolest Science Merchandise of 2019 - December 16, 2019

- Science Media Centre (UK) offers guide on dealing with online harassment in academia - November 26, 2019

- Agile project management taught to students and researchers at Karolinska Institutet - September 20, 2019

- Stefan Jansson: Improve your credibility! (Crastina Column, September 2019) - September 6, 2019

- The People’s Poet: Silke Kramprich, tech communicator - August 31, 2019

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!