Amanda Montañez: “Cajal is an icon in the field of scientific drawing”

The Nobel Prize winner Santiago Ramón y Cajal is often mentioned as a researcher who used his drawing skills extensively to make scientific progress. Medical illustrator Amanda Montañez describes why.

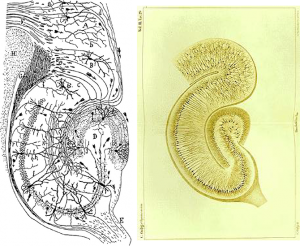

In a blog post at Scientific American, medical illustrator Amanda Montanez recently explained why Cajal is a perfect example of how of scientific discovery “has hinged not just on our ability to see certain things, but also on our capacity to reproduce what we see in faithful, critical and/or meaningful ways”.

As sketching and drawing is our theme this month (link 1, link 2), we got in touch for some questions.

Hi, Amanda! How come Cajal has earned such fame in the field of scientific sketching and drawing?

I think Cajal is an icon in this field for a few reasons. First, his big discovery—the neuron doctrine—was so important scientifically. He is known as “the father of modern neuroscience” because the neuron doctrine virtually redefined how scientists studied and understood the nervous system. But moreover, his drawings are so wonderfully instructive. Without these drawings, his discovery still would have been monumental, but with the drawings, he was able to communicate his ideas visually as well as verbally. Other scientists did not just have to take his word for it; they could actually see why his ideas made sense.

I think Cajal is an icon in this field for a few reasons. First, his big discovery—the neuron doctrine—was so important scientifically. He is known as “the father of modern neuroscience” because the neuron doctrine virtually redefined how scientists studied and understood the nervous system. But moreover, his drawings are so wonderfully instructive. Without these drawings, his discovery still would have been monumental, but with the drawings, he was able to communicate his ideas visually as well as verbally. Other scientists did not just have to take his word for it; they could actually see why his ideas made sense.

Of course, the drawings are also beautiful. There is quite a history of drawing in neuroscience—the amazing complexity of the nervous system lends itself to art making—and Cajal, in his artistic brilliance, was one of the first to capture it in a way that was as visually elegant as it was didactic.

Why should this concern the early career scientist?

The idea of drawing in science feels a bit antiquated nowadays because we have such advanced imaging techniques available to us. It’s easy to get excited about all of the ways we can capture images of things we’ve never been able to see before. But I think scientists should be careful not to abandon the practice of drawing from observation, because it requires a way of examining and interpreting things that even the highest resolution, most detailed photograph cannot evoke.

The idea of drawing in science feels a bit antiquated nowadays because we have such advanced imaging techniques available to us. It’s easy to get excited about all of the ways we can capture images of things we’ve never been able to see before. But I think scientists should be careful not to abandon the practice of drawing from observation, because it requires a way of examining and interpreting things that even the highest resolution, most detailed photograph cannot evoke.

When people ask me about the advantages of medical illustration over photography, I often use the example of surgical illustration. A photograph of a key moment in a surgical procedure may show surprisingly little discernible information. Distracting visual elements, like blood and instruments, may dominate the visual field, making it difficult to understand what is happening in the image. A well-executed illustration of the same moment tells the story much more successfully because the artist highlights the key structures and actions while toning down or filtering out a lot of the visual “noise.” This of course makes the image much more accessible to the viewer, but interestingly, it also forces the artist to study and analyze a great deal of information. In describing the procedure visually, the artist becomes intimate with its details in the same way a literary translator becomes immersed in the text she or he is rendering.

Which three lessons can be learned from Cajal’s work for modern scientists who want to use drawing and sketching as a tool?

Which three lessons can be learned from Cajal’s work for modern scientists who want to use drawing and sketching as a tool?

1) Drawing can help to bring a scientist closer to a subject of study, but more than that, it can lead to important discoveries. Cajal’s intense dedication to observing and drawing neurons was a key part of the process that led him to the neuron doctrine.

2) It’s not enough to draw something once. Cajal made hundreds of drawings throughout his study of the nervous system. No matter how well you think you understand something, more drawing is always better!

3) Don’t be afraid to draw because you think you’re not good at it. Even though Cajal happened to be a talented draftsman, I don’t think it was his artistic prowess that made his study so successful. It certainly helped him communicate his ideas better, but in terms of bolstering his own understanding of how neurons worked, it was the process of drawing, rather than the beauty of the end product, that yielded the greatest benefits.

Read more about Amanda Montañez on her personal website.

- Claire Price of Crastina receives outreach award from Royal Society of Biology - October 25, 2020

- Agile Science student project at Brussels Engineering School ECAM: “We can’t wait to try it again!” - August 28, 2020

- Create an infographic in the Lifeology SciArt Infographic Challenge - June 16, 2020

- Adam Ruben – The scientist that teaches undergraduate students comedy - March 27, 2020

- Sam Gregson, Bad Boy of Science: “Comedy helps to bridge the gap” - March 10, 2020

- The Coolest Science Merchandise of 2019 - December 16, 2019

- Science Media Centre (UK) offers guide on dealing with online harassment in academia - November 26, 2019

- Agile project management taught to students and researchers at Karolinska Institutet - September 20, 2019

- Stefan Jansson: Improve your credibility! (Crastina Column, September 2019) - September 6, 2019

- The People’s Poet: Silke Kramprich, tech communicator - August 31, 2019

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!